By Carol Yuen, LVF Stewardship Committee Member and LLM in Environmental Law and Policy candidate at UCL, 2024/25

SOIL: The World at Our Feet, held at Somerset House, was an exhibition to unearth soil’s vital role in our planet’s future. LVF members visited together on 30 March 2025. The exhibition was an excellent combination of art and science, aesthetic and educational at the same time, giving us the opportunity to consider the importance of soil.

When we think of soil, we tend to think of dirt. But under the microscope, we see soil full of many microorganisms; a very diverse ecosystem. These microorganisms are vital to sustaining the life systems on Earth.

The exhibition started with artworks that allowed the audience to peer within the soil. We were invited to pause and sense what was beneath our feet. I imagined the soil underneath me, teeming with life, as I revelled in the striking close-up photography depicting micro-organisms. The microbial activity is invisible to the human eye, but the systems of connection between the creatures, roots, fungi and plant life are intricate and connected via the soil. We had the chance to look at them from a microscopic viewpoint, through hanging tiny ceramic pieces of microbes and through a digital luminescent video. These different media allowed us to connect in a way that we resonated with most. For me, I thought the photography was immensely striking and gave me the feeling of wonder looking at a planet in the solar system, when we were in fact looking beneath the soil.

The photographic prints, titled ‘This Earth’, by Daro Montag (2006) were created by placing soil samples in contact with moistened colour film, allowing microorganisms in the soil to leave traces of their activity. Montag described his work as showing the vibrancy of living soils; that soil is not a dead matter but a complex living organism.

Through these pieces, we understood that soil supports plants, stores carbon and holds water. In the context of our fight against the climate crisis, soil plays a very crucial role.

The second part of the exhibition upstairs made us look at the broader landscape surrounding soil, featuring more conceptual and contemporary artwork. We saw how soil has been, for centuries, intricately connected to our culture and society.

This segment started off with a rather incomprehensible display of a sword from ancient times. A close reading of the description, however, revealed that peatland soil (where organic soil is formed in waterlogged conditions) has the perfect conditions to preserve archaeological treasures like this word, because material – including dead plants – decompose slowly. This is also the reason why peatlands store vast amounts of carbon, because the dead plants have absorbed carbon from the atmosphere and will continue to do so for a long time. Hence soil is a crucial carbon sink and useful resource in combating the climate crisis.

Among the many artworks displayed, a couple stood out for highlighting the social injustice connected with soil and land.

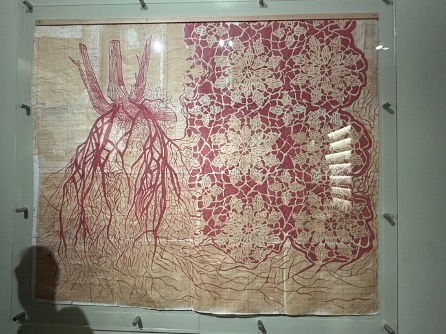

Annalee Davis’s works on ‘unlearning the plantation’ (2015;2022-2023) are related to her experiences of living and working on a former sugar plantation in Barbados, where the soil holds memories of extractive colonial violence inflicted on the enslaved people and the land they were forced to tend. While there was value in the biodiverse plots of land, they were situated within the capitalist machinery of the plantation. The sugar cane structure stretches across the surface of a plantation paylist, while the resemblance of the roots to human lungs alludes to the climate crisis. The work alluded to both historical and contemporary concerns, as we continue to grapple with neocolonial exploitations of soil.

Greek-Palestinian artist Theo Panagopoulos’ short film ‘The Flowers Stand Silently Witnessing’ (2024) shows archival footage of wildflowers in Palestine in the 1930s, signifying the entanglement of people and land ‘currently being dehumanised’. This was a popular film in the exhibition, with many visitors staying to watch it for a long time. The film was silent yet poignant, using the soil and flowers to tell a story of dispossession.

Asunción Molinos Gordo’s ‘Ghost Agriculture (Unlimited Resource Farming)’ (2018) featured patchwork on Egyptian patchwork that featured geometric patterns based on satellite images of the Nile Valley. While the thousands of small rectangular plots of alnd not larger than 100 square metres show cultivation by agricultural labourers and natural, renewable irrigation from the Nile, the large circles of agricultural plots are huge farms with an average radius of 2.5 kilometres which are irrigated by non-renewable fossil water via underground aquifers using sprinkler systems. The smaller farms produce food for national demand, while the larger farmers export to the international market and are run by a handful of private companies. For me, the juxtaposition of geometric patterns starkly highlighted the vast difference in treatment of the land and water by farmers and by large agricultural companies.

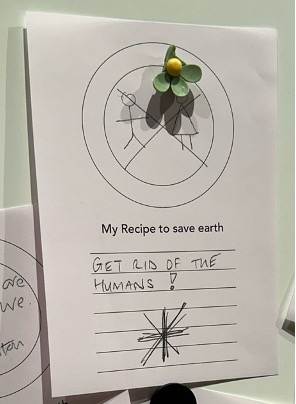

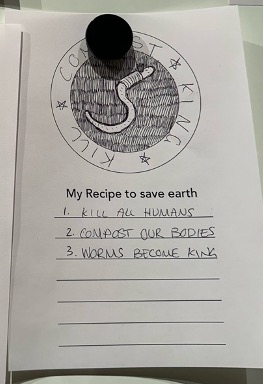

The display of the activities within and around the soil made me think deeply about the importance of soil. I’m sure the other visitors did too, as we saw hilarious yet serious responses at the end of the exhibition to the prompt “My Recipe to save earth”.

We are only a tiny part of the planet’s complex ecosystems. As the exhibition called for, thinking about soil allows us to reconsider our relationship with the soil and build reciprocal connections, differently from the extractive associations that we’ve historically had with soil.

What do we feel beneath our feet when we step on soil? Dirt, or life?

SOIL: The World at Our Feet was curated by Henrietta Coutault and Bridget Elworthy, in collaboration with Somerset House Trust’s Claire Caterall and May Rosenthal Sloan and ran from 23 January to 17 April 2025.

Leave a reply to May 2025 Newsletter – Legal Voices for the Future Cancel reply